The Sunk Cost Fallacy

Why we don't quit (even when it's obvious we should).

Hey friends.

How many times have you finished a movie and thought, “I should have stopped after the first 10 minutes!”? We’ve all been there, and that means we’ve all fallen prey to the sunk cost fallacy.

This cognitive bias can have worse repercussions than enduring a bad movie (although having to watch The Rise of Skywalker is a pretty bad consequence), so in this article, we’ll go over what it is, common ways to fall into it, and how to avoid it.

Let’s dive in.

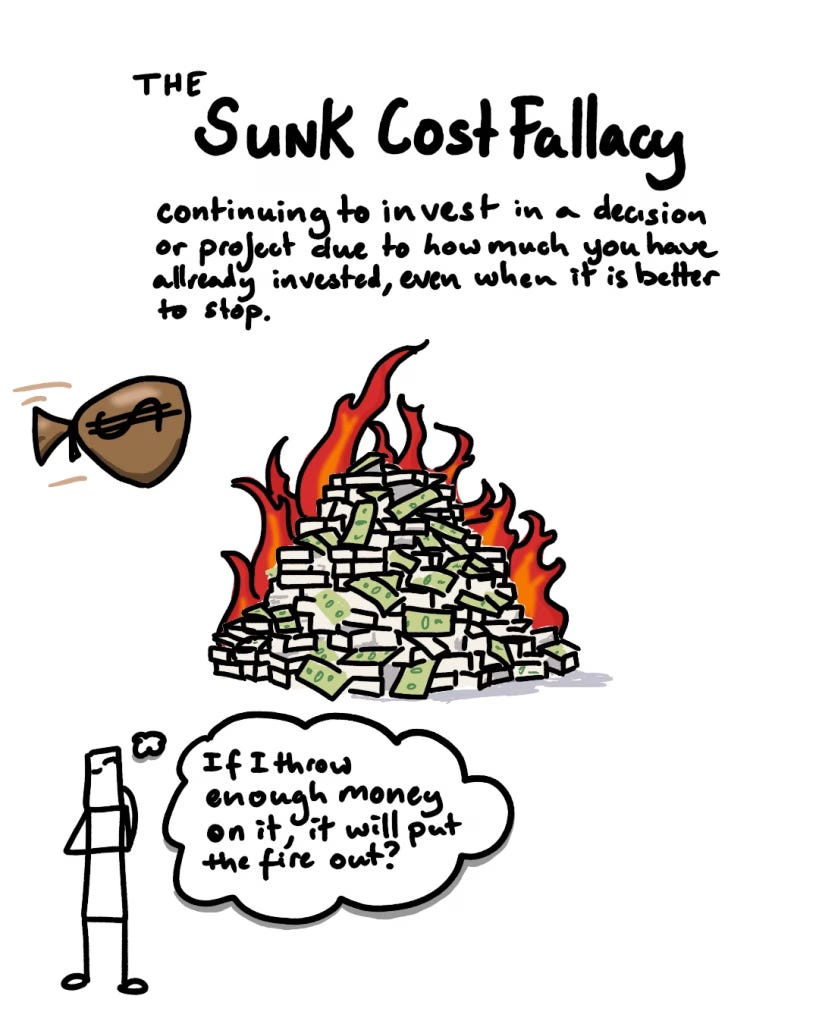

What is the sunk cost fallacy?

The sunk cost fallacy is a cognitive bias when we spend more time, money or effort on something because we have already invested so much even when it would be better to quit and invest somewhere else.

Here’s a common example.

Let’s imagine you’re a company with a top secret project X. You anticipated that it would cost you $1 million and a year to make it happen, with returns of $5 million. But it doesn’t work out that way. A year passes, and it’s still not ready. Now, you’ve already spent $2 million, and it looks like you need another year and another $2 million to finish it.

The smart thing to do would be to imagine what the best investment of $2 million and a year’s work would be, rather than just carrying on with what you’ve already invested in. And yet, 90% of us would just carry on, not just because we started, but because we’ve invested so much time already.

It doesn’t just apply to business investments; it can also apply to:

Career — Instead of changing jobs, we stay in a familiar one

Books and media — We refuse to switch books or movies even when we hate them.

Relationships — We carry on in unhappy relationships because to separate would mean we’d have lost so much time.

Why does it matter?

The sunk cost fallacy has two related consequences.

It makes us waste time, energy and money on projects we shouldn’t

It makes us miss other, better opportunities that are available.

These are directly related, but each on its own is a worthy reason to avoid its effects.

In the best case, we might carry on with a project or task that takes longer than we predicted, but we still get to the end. In the worst case, we can throw more and more at a losing situation where nothing would affect it.

Seeing things as they really are helps us avoid both.

How does it work?

The sunk cost fallacy is caused by focusing on the past, not the future.

Instead of accepting that the money and time we’ve already spent are gone, we keep them in our minds and make our decisions focused on them. We irrationally hope that by holding on to that investment, we can earn it back.

It’s not always the wrong thing to do.

After all, if the results are high, then it should require less effort to get our desired outcome than starting from scratch. (i.e. If you've half finished writing an essay, you should need less time to finish it than to start again).

The trouble comes when the situation changes or our initial assumptions turn out to be incorrect. That's why we need to step back and weigh up the cost-benefit again.

It's also related to several other cognitive biases, including:

Consistency/commitment bias - We stick to what we have committed to do.

Loss aversion - We view losses as worse than gains of equal value.

Cognitive dissonance - We feel uncomfortable with evidence that goes against our view of ourselves.

Status quo bias - We have a bias to stick to the status quo.

[Would you like to know more about one of these biases? Let me know in the comments.]

How to avoid falling prey to the sunk cost fallacy?

Let's start by being practical here — some decisions are more important to get right than others. Those are the ones where you really need to apply these tools.

For smaller decisions, some of the ideas I'll share can help you develop good habits that you can use in other situations, but if you don't get everything right, that's okay.

The point isn't to make perfect decisions, but better ones.

With that in mind, here are a few simple principles.

Ask yourself, "Would I start this again today?"

Focus on what you need to do next, not what you have already done

Consider what else you could invest your time or money in.

Get used to quitting — practice with bad books or films is a great way to start. It's not a sign of failure, but wisdom.

Before you start a new project, set checkpoints and criteria to help evaluate your actions.

None of these are foolproof, but they can help you focus on making informed, not ignorant, decisions.

Conclusion

It’s not a mistake to pick the wrong option, it is a mistake to keep investing in it.

Understanding the sunk cost fallacy and focusing on the situation as it is now, not when you first made a decision, can help you avoid this mistake. But as with all things, give yourself some slack.

We all make mistakes, like picking a bad movie. Hopefully, you can gain some joy by sharing your frustration with some friends.

Optimism bias, Framing bias, Recency bias, Planning fallacy, Loss aversion

...and thanks for the article, too