7 mental models Jeff Bezos uses to run Amazon

As I write, Amazon is the 5th most valuable company in the world with a market cap of 2.3 trillion dollars.

How did the founder and CEO grow it from a garage in Seattle to the giant it is today?

Well, here are five mental models Jeff Bezos swears by (some he invented) that have helped drive its success.

Regret Minimisation Framework

Imagine you’re facing a scary decision: what to study, whether to move country, or if you should accept a job offer.

How would you make that decision?

Well, Jeff Bezos created a mental model just for these kinds of decisions that he personally faced.

He picks the option that will lead to the least amount of future regret.

Let’s imagine you have the opportunity to take a job overseas for a year with your comapny.

Using regret minimisation, you imagine yourself 5/10/50 years in the future and wonder if you’ll regret it more if you take the opportunity or not. You’d probably regret not taking it (although, you might have other factors going on that would cause you to regret not staying that year too, such as spending time with a dying family member or a local exciting job offer).

Why this is a great mental model

Regret minimisation helps you get over the fear and self-doubt of a decision and focus on the opportunities. It also helps avoid focusing on the likelihood of certain outcomes when so much is unknowable.

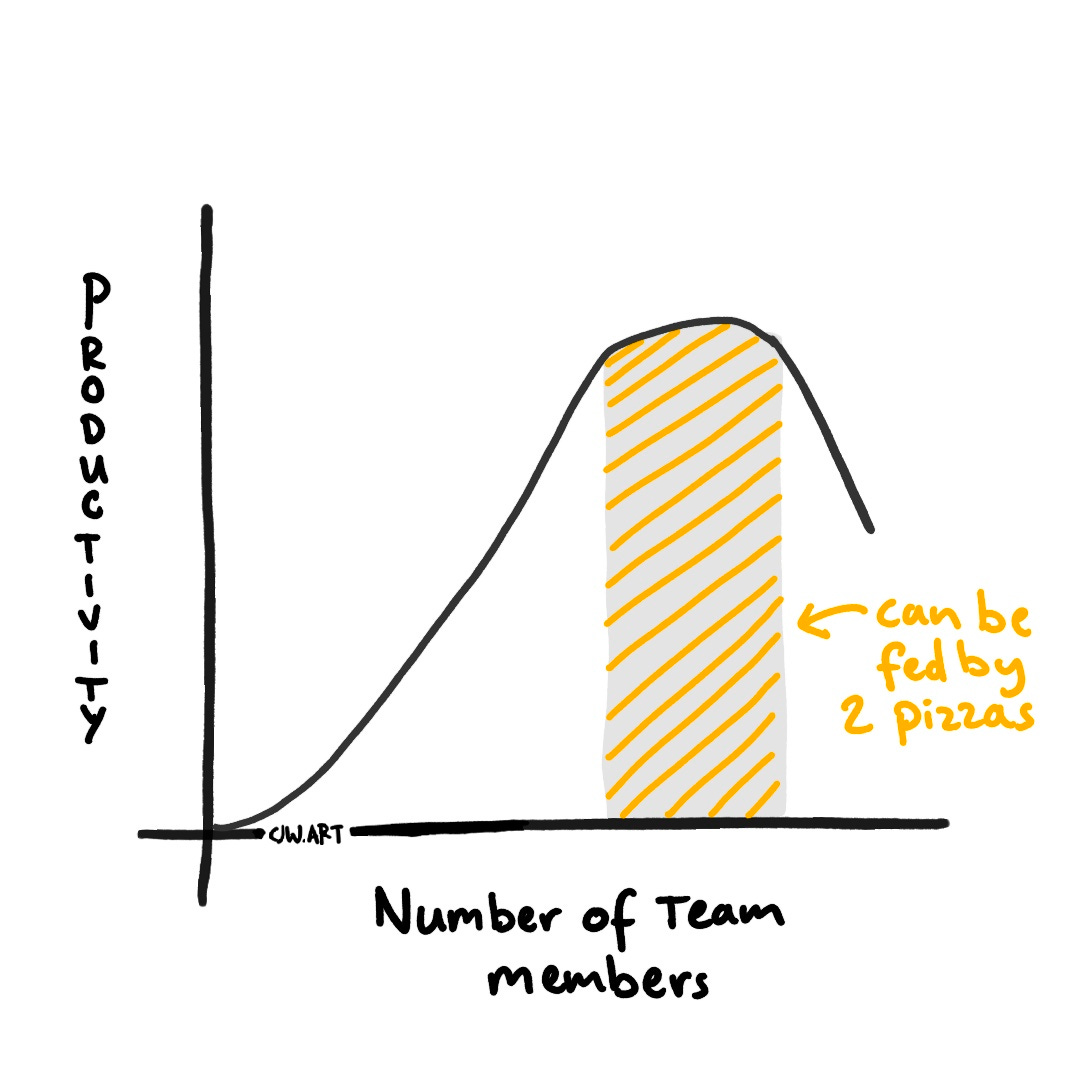

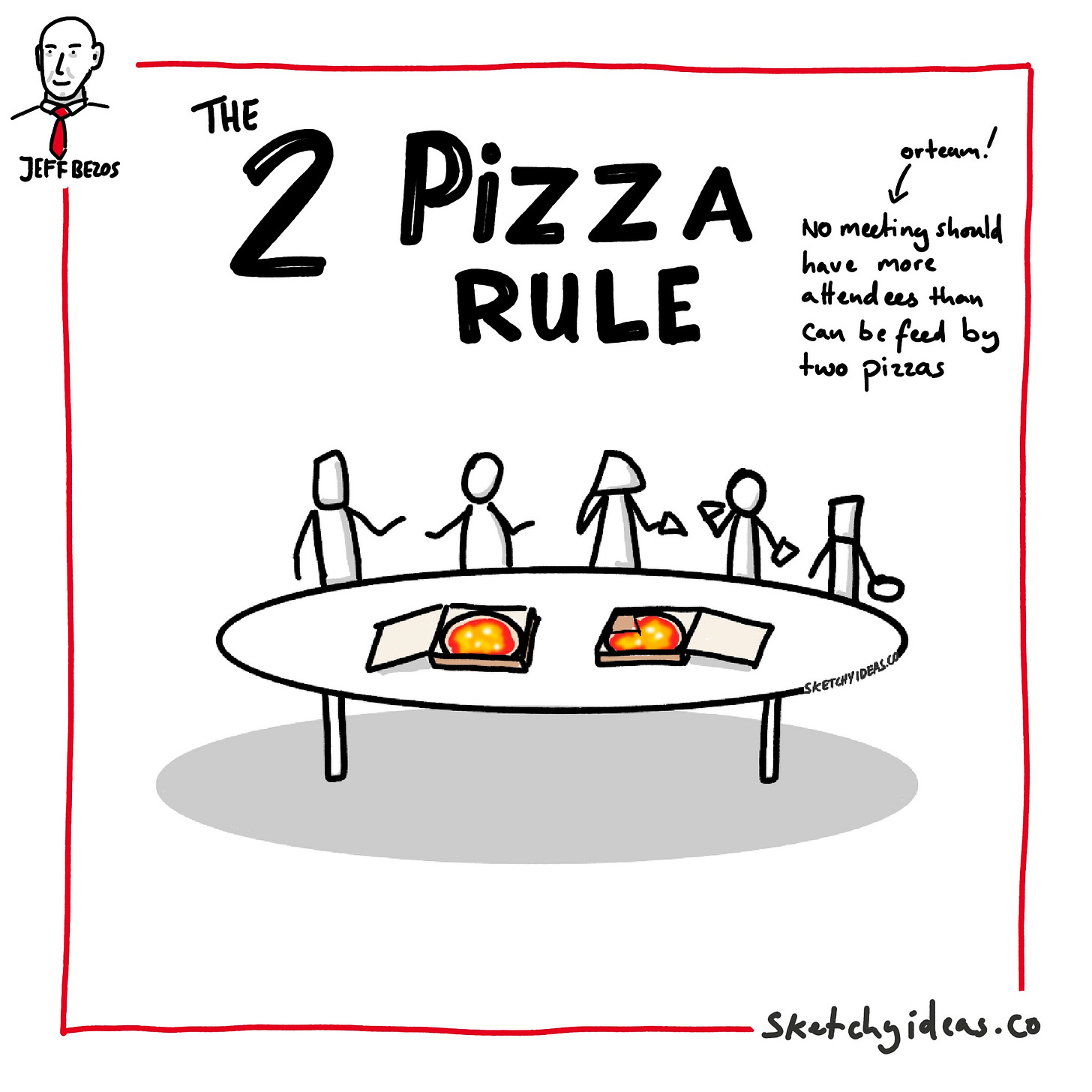

The Two-Pizza Rule

Ever been in a meeting and thought, “Why am I even here?”

We’ve all been there, and when a meeting is too big, it’s a waste of everyone’s time. It often leads to bike shedding, where little details are debated in too much detail. And even when it doesn’t, it prevents people from using their time more effectively.

To combat this (and improve collaboration in teams), Jeff Bezos coined the two pizza rule.

Teams (and meetings) should be small enough to be fed by two standard pizzas so they are small a nimble enough to collaborate together.

No meeting, nor team, should have more members than can enjoy two pizzas as a meal together.

In practical terms, that’s about 6 to 10 people (depending on how hungry you are!).

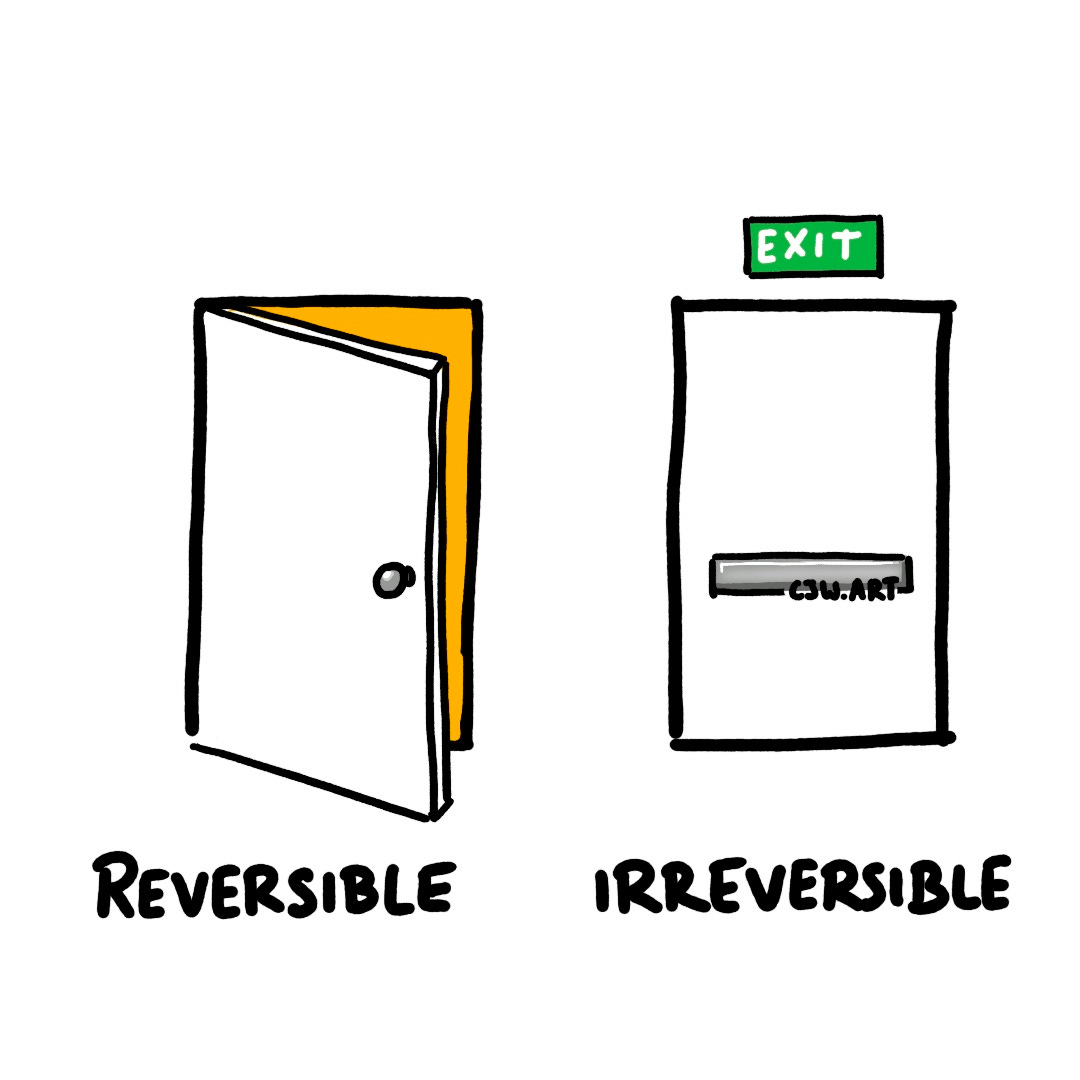

Reversible vs Irreversible Decisions

We can waste a lot of energy thinking about unimportant decisions, but how do you know when you should just make a decision quickly?

The framework of reversible vs irreversible decisions can help.

Most decisions can easily be reversed, but some are irreversible.

When a decision has a low probability of negative impact and can be easily reversed, you should approach it quickly. When it has high risks and is hard or impossible to reversible, approach it slowly.

When we make reversible decisions quickly, we can use them to gather the data we need to then evaluate the success of that decision. Something that is far harder to do without data in the first place.

Anecdotes over data

Imagine you have a couple of customers complaining that your website is loading slowly, but when you look at your load time reports, it says everything is fine.

What should you believe?

Jeff would say the people and he described why on the Lex Friedman podcast.

“I have a saying which is: When the data and the anecdotes disagree, the anecdotes are usually right.

It’s usually not that the data is being miscollected. It’s usually that you’re not measuring the right thing. If you have a bunch of customers complaining about something, and at the same time your metrics look like they shouldn’t be complaining, you should doubt the metrics.

This model highlights the strengths and weaknesses of data.

While data is objective, it’s only as effective as what it measures. In our website load example, it might be that the customers are using a very specific setup that is causing issues, or that the load times recorded don’t account for a process on the customer’s computer that happens first.

Either way, you should never dismiss anecdotes out of hand.

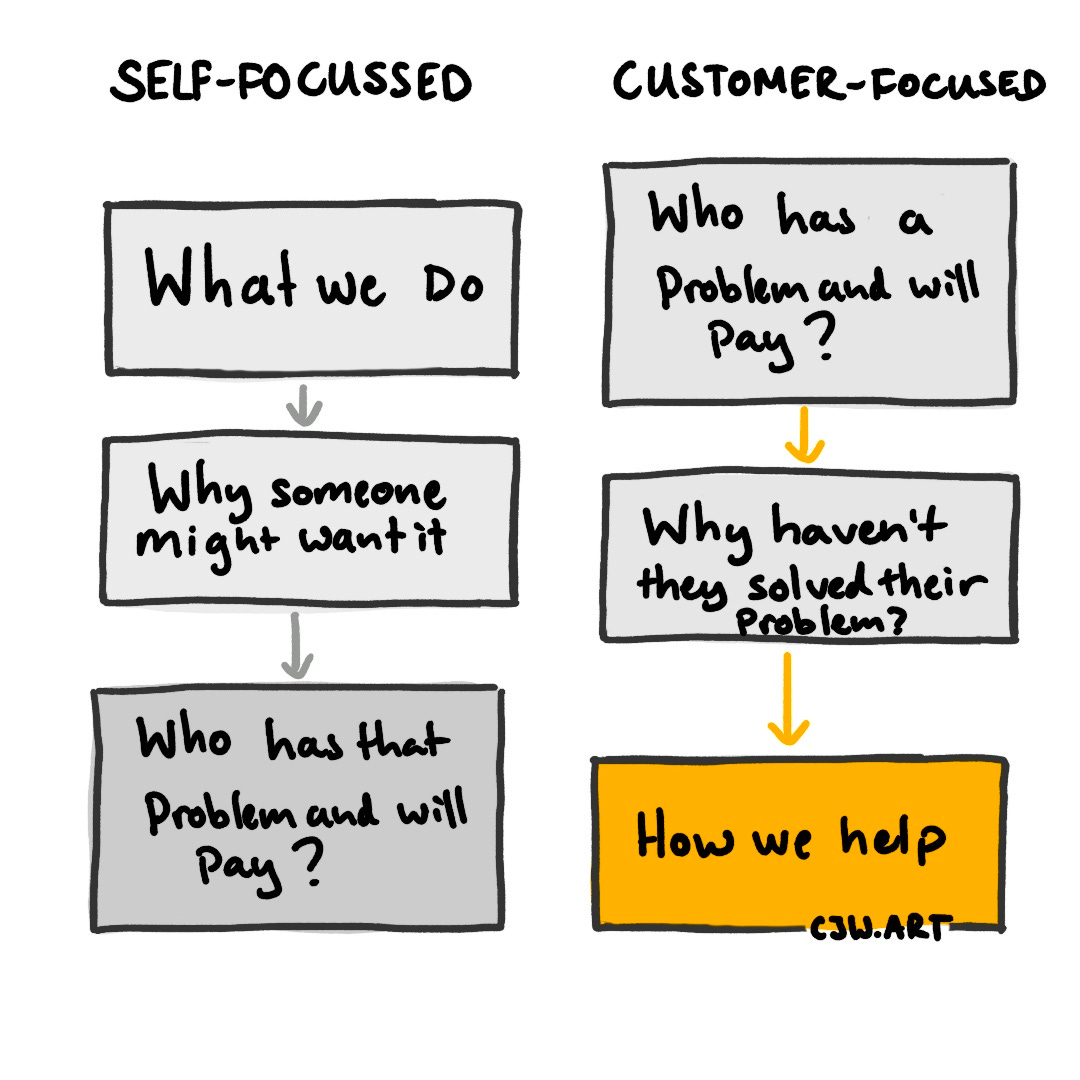

Work Backwards from the Customer

“That sounds like a solution in search of a problem.”

Ever heard this? It’s a trap many businesses fall into. Some new technology or innovation comes out (*cough* generative AI *cough*) and all of a sudden, you can’t buy a kitchen appliance without it offering to write your emails for you.

But it’s not just technology companies; it can also be creators and entrepreneurs. We can focus on our skills and abilities and try and force people to pay for them.

Jeff has made Amazon famous for starting with the customer’s needs and then creating solutions to match. Working backwards means you focus on real needs that people are actually trying to solve. And that means people will actually pay for what you deliver.

If you like to learn more about this process, check out my sketchnote summary of the book “The Mom Test“.

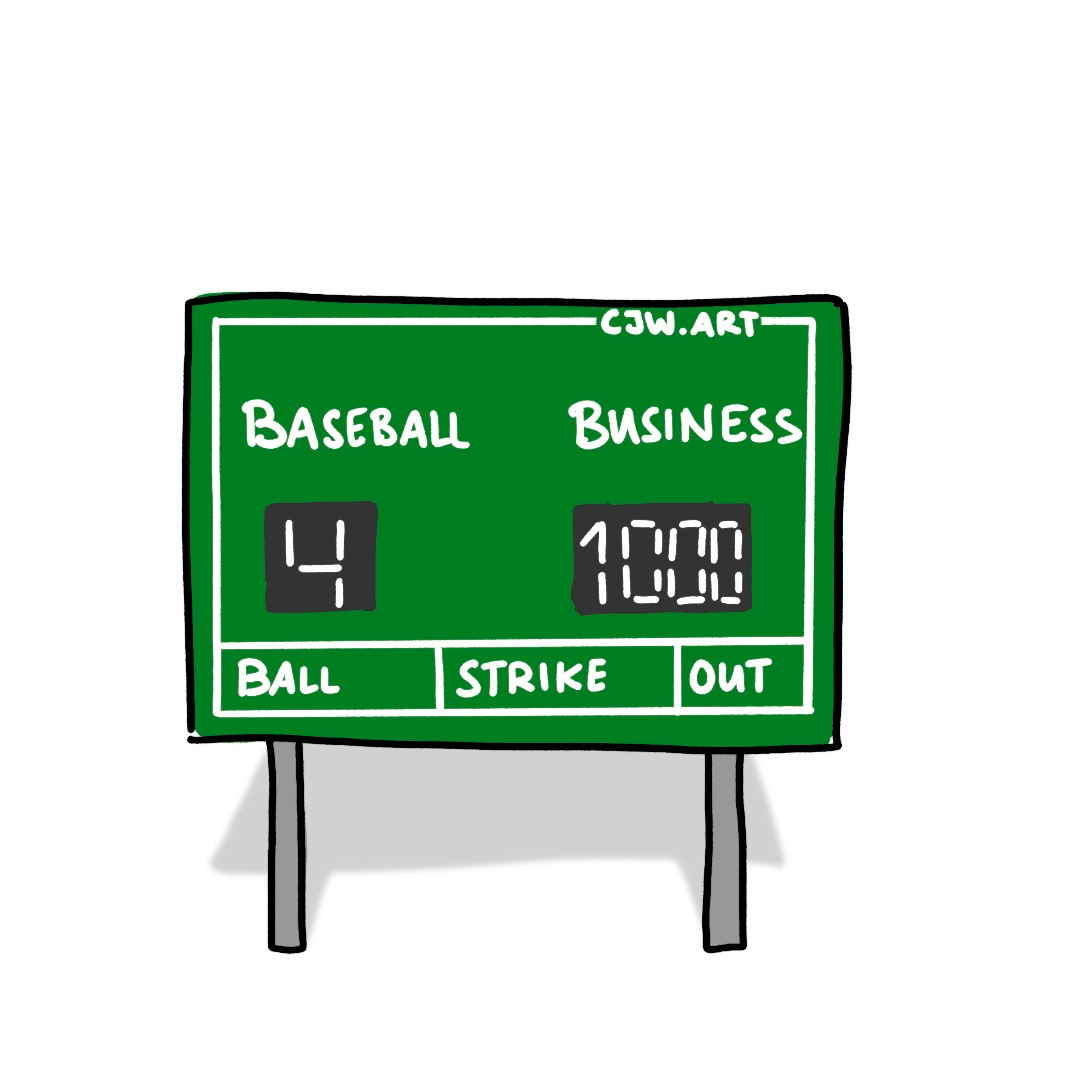

Winning in Baseball vs Winning in Business

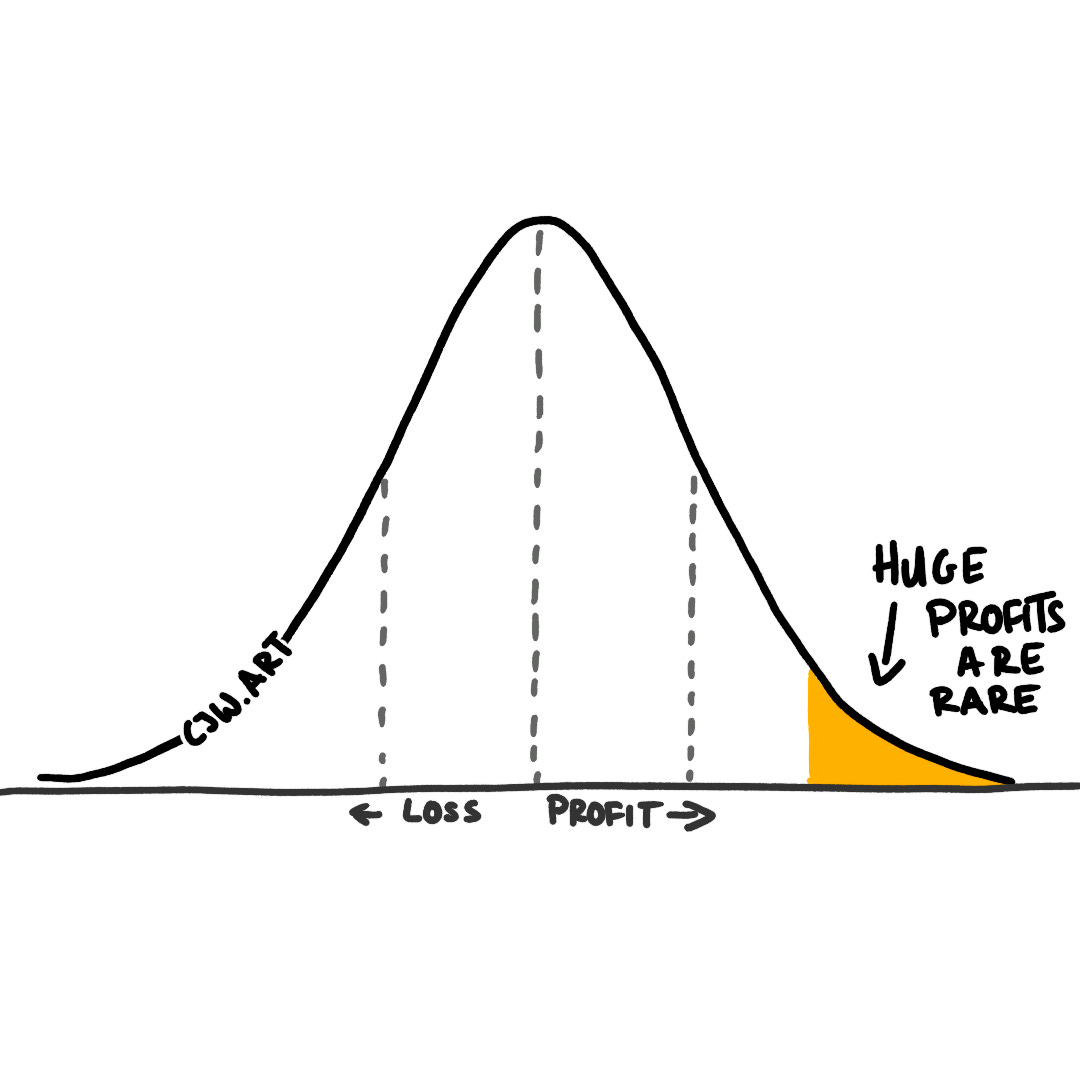

Sports have regular returns, but business often has outsized returns for the best — it’s a long-tail distribution game.

That means if you do the same as everyone else, you’ll probably achieve modest returns. Taking the unconventional path, however, can lead to exponential returns as well as big losses.

That’s why Amazon tries so many experiments.

Here’s how Jeff describes it.

Outsized returns often come from betting against conventional wisdom, and conventional wisdom is usually right. Given a ten percent chance of a one hundred times payoff, you should take that bet every time. But you’re still going to be wrong nine times out of ten.

We all know that if you swing for the fences, you’re going to strike out a lot, but you’re also going to hit some home runs. The difference between baseball and business, however, is that baseball has a truncated outcome distribution.

When you swing, no matter how well you connect with the ball, the most runs you can get is four. In business, every once in a while, when you step up to the plate you can score one thousand runs.

This long-tailed distribution of returns is why it’s important to be bold. Big winners pay for so many experiments.

Another approach to this is the “small bets” mindset of Daniel Vassallo. Instead of investing heavily in one area, you keep creating small bets, waiting for the one that massively takes off.

Missionaries vs Mercenaries

When I meet with the entrepreneur who founded the company, I’m always trying to figure out one thing first and foremost: Is this person a missionary or a mercenary?

The mercenaries are trying to flip their stock. The missionaries love their product or their service and love their customers, and they’re trying to build a great service.

By the way, the great paradox here is that it’s usually the missionaries who make more money, and you can tell really quickly just by talking to people.

This idea comes out of the distinction between intrinsic and extrinsic motivations.

Intrinsic motivation is when the act of doing something is its own reward. I.e. You play the guitar because you love to make music. Extrinsic motivation is when you do something for a reward (or to avoid a punishment), not tied to the action. I.e. you practice the guitar because your parents pressure you to, pay you if you do, and you need to in order to get a good grade.

You might think that extrinsic motivation is more effective, but studies have shown that intrinsic motivation is more effective.

That’s why it pays to notice what is motivating an entrepreneur or employee.

Which of Jeff Bezos’ Mental Models do you like?

Jeff has talked about other mental models he uses, but these are some of my personal favourites (especially regret minimalisation). I’d love to know what your favourites are, even if it’s one of his that I haven’t included.

And you can help others discover them by liking and sharing them on

Thank you

Want to share ideas that matter to you? Sign up for this free email course to learn how to draw anything (sketchily) in just 5 days.

Or if you’d like me to sketch your ideas for you, check out my services.

And if you’d like a different topic visualised in the future, let me know what you’d like to see!

Another lesson from Bezos I like is how he talks about the importance of rethinking your ideas and beliefs from time to time:

“People who were right a lot of the time were people who often changed their minds.”

Why using pizzas instead of just counting if you have a lot of tiny people in your team the rule might not work